In Real Life.

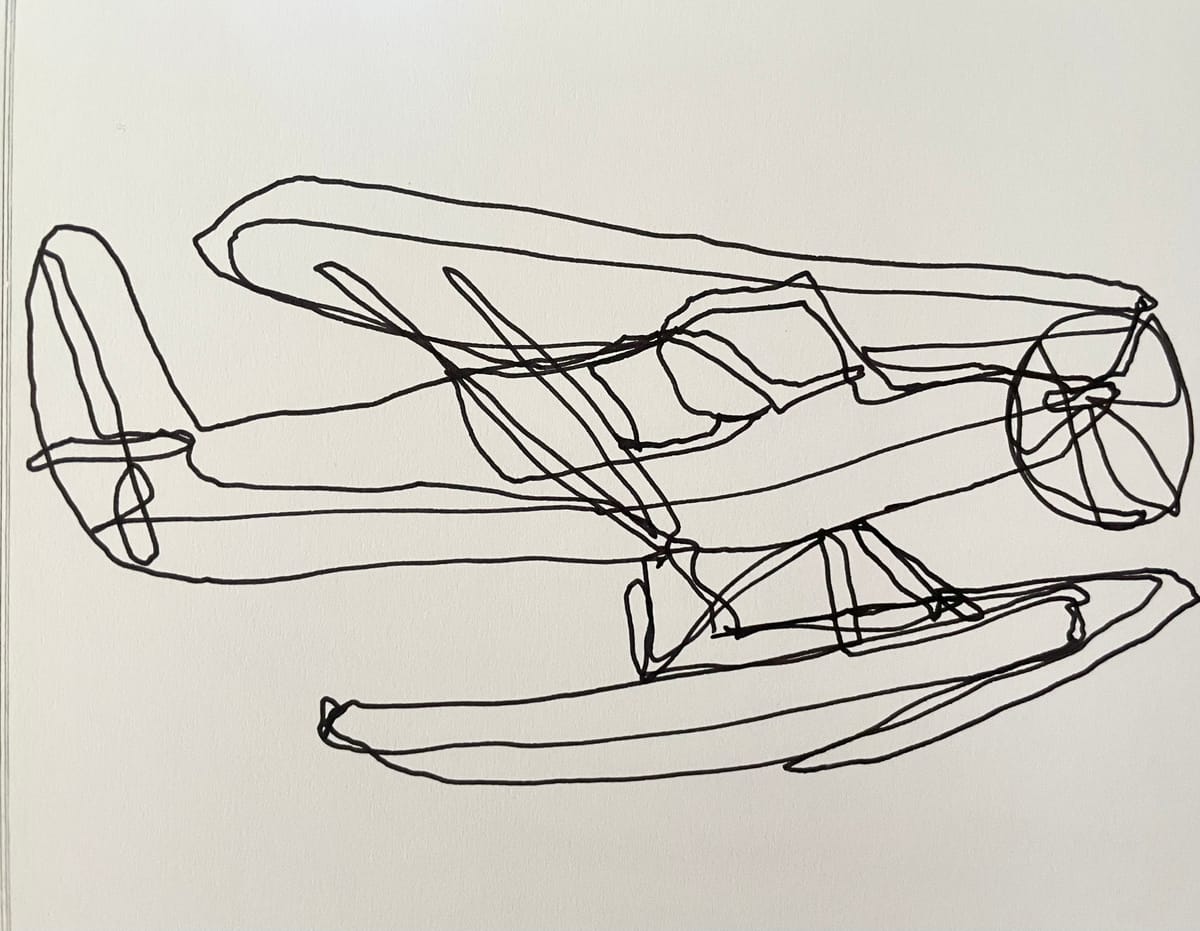

It’s 8am. I’m waiting to board a float plane. I interpret them as lacking self confidence, built to fly, with landing equipment appendages that look like an afterthought on any normal plane, yet now accentuated by canoes strapped to each foot. It delivers on its promise, it floats, and flies, but not without effort- a screaming engine to remind you that water is something of resistance to objects that insist on momentum. Eventually, a surreal scene of the canoes gliding through the sky takes me in. With the clouds, I reflect on lived experiences. It is so good to be in the world, to see the land and sea zip past and hear the noise of the engine scream. I had turned off communication from the world for the last 10 days, and I believe I achieved some kind of dopamine reset, trading being here instead of being with the machine.

I relished the analog experience. I took photos with a film camera, read the Atlantic in print, played games with cards and entertained children (and myself) with wooden toys and found sea glass. I re-discovered the mechanics of reality- a clicking shutter, changing a tire, cold swim, long walks. And I in no way missed the artificial engagement with the online, as I had expected to. The behavioural trained dopamine reactions, I had assumed a sense of loss and longing for daily impulse to check things. I did not. A desire to check in was easily replaced by a desire to look out of a window, seek birds, chop fruit, hold a hand, read a leaflet.

Behind the scenes of my very physical experience of being in real life, I notice the psychological experience that exists just beyond. Easily as physically abstracted as my left behind online world, this world lives in my own perception of things. And these things felt slow. One task in the real world takes a real amount of time to set up in a physical environment. Switching tabs in real space is a process. To move from changing a tire to going for a walk to sitting down with a magazine takes a physical experience that moves you through space- rather slowly. Time is at the mercy of space in real life. And as a result, thoughts and psychology are gifted the liberty of time.

Spelt out and articulated, am I stating the obvious, or have others like me lost this simple truth?

In real life, the float plane really grabs my attention. It’s wonderfully present to me- a physically intriguing form and function to see, a strong smell, a loud noise. This object of little self confidence performs a defiant feat of transportation. I liked them immediately. Made for one task, adapted for another, and serving a purpose that didn't need any more ability than the paper mache equivalent of its aviation cousins. And in that moment in real life, with the luxury of time, I’m wondering if I am the float plane.

As I relate to this machine, I ponder career change- designed for one thing, adapted to another- strapping canoes to my feet to function on new bodies of water, desperate for forward momentum, with a little engine screaming in rejection but somehow confident in its task. At the end of the waterway—surprised—by flight. I wonder if this human machine interaction I’m having is a strange one. How in this moment this human made object lifts me into a human experience. I decide not, we're humans after all. Tools are our things, an extension of who we are. But for the float pane I’m grateful for its directness and humility. It exists in a simple sense. Newer machines that are more deeply integrated extensions of both my physical and phycological self are far less sincere. For one, they lack experiential intrigue I’ve rediscovered in real life. They are deceptive, highly well presented, and have a knack of moving me away from myself.

It's a difficult task lately to be a float plane in real life.